The 4th of July

Every year the 4th of July gives Americans the chance to think about our roots and hopefully show a little gratitude for the sacrifices that a lot of people made for us. Unfortunately gratitude is not a common virtue among a large segment of our ill-informed fellow citizens who do not even know who fought in the revolutionary war, the civil war, or World Wars I and II.

Instead this year we are witnessing citizens who are inflamed about racial tension and are willing to disregard our entire history of progress to satisfy their sophomoric notions of history. In their eyes, the founding fathers where evil slave owners, not worthy of our admiration or gratitude.

We can only ask them to consider the thousands of our compatriots who followed those founding fathers and became the soldiers who delivered victories that resulted in the preservation of that same Liberty we all share.

Baltimore Independent Cadets

On December 3, 1774 the Baltimore Committee of Observation and 59 Baltimore citizens formed the Baltimore Independent Cadets and elected Mordecai Gist to be their Captain. They adopted the following bylaws, which explain their purpose.

“We, the Baltimore Independent Cadets, deeply impressed with a sense of the unhappy condition our suffering brethren of Boston–of the alarming conduct of General Gage–and the oppressive unconstitutional acts of Parliament to deprive us of liberty, and enforce slavery on his Majesty’s loyal liege subjects of America in general; for the better security of our lives, liberties, and property, under such alarming circumstances, think it highly advisable and necessary that we form ourselves into a body or company, in order to learn military discipline, and to act in defiance of our country, agreeable to the Resolves of the Continental Congress. And first, as dutiful subjects t King George the 3rd, our Royal Sovereign, we acknowledge all due allegiance, freedom and liberty of the Constitution. Secondly, we resolve after a company of sixty men shall have voluntarily subscribed their names to this paper, that public notice thereof shall be given, and a meeting called to elect the officers of said company, under whose command we desire to be let, and will strictly adhere to, under all the sacred ties of honor, and the love and justice due to ourselves and country; and in case of any emergency we will be ready to march to the assistance of our sister colonies, at the discretion and direction of our commanding officer so elected, and that in the space of forty-eight hours notice from said officer. Thirdly, we agree and firmly resolve to procure at our own expense, a uniform suit of clothes, (Regal.) Scarlet, turned up with buff, and trimmed with yellow metal, or gold buttons, white stockings, and black cloth half boots; likewise, a good gun with cartouche pouch, a pair of pistols, belt and cutlass, with four pounds of powder and sixteen of lead, which shall be ready to equip ourselves with, on the shortest notice. And if default shall be found in either of us, contrary to the true intent and meaning of this engagement, we desire, and submit ourselves to a trial by court martial, whom we hereby fully authorize and empower to determine punishments, adequate to the crimes that may be committed, but not to extend to corporal punishment. Given under our hands, this third day of December, in the year of our Lord, one thousand seven hundred and seventy-four.”

The Baltimore Independent Cadets, were absorbed into William Smallwood’s Maryland Battalion (or Regiment) and into seven attached independent companies on January 14, 1776. Compared to the rag-tag Colonial soldiers, the Cadets were elegant in their uniforms and rifles with bayonets. The contrast earned them the name Macaronis, similar to our word “dandy” now. It was used pejoratively referring to solders who excelled in appearance, discipline, and ultimately in performance on the battlefield.

In July, 1776, the Battalion was assigned to the main Continental Army and formally adopted into the Continental Army in August. Later that month, the first and largest battle of the Revolution was fought on the west end of Long Island and is variously called the Battle of Long Island or the Battle of Brooklyn.

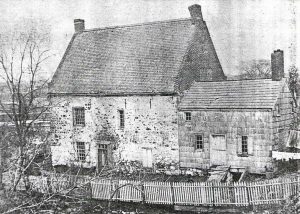

Old Stone House

An Old Stone House was a central feature of the Battle of Brooklyn. The British General Cornwallis occupied the house as his headquarters. At the time of the historic battle, the British greatly outnumbered Washington’s army so he ordered their retreat. Brigadier General William Alexander Stirling fought on for several hours not realizing that he was being outflanked by the British.

When he saw he was surrounded, Stirling ordered his men to retreat also, but they were essentially cut off. A few escaped though a swamp but many were killed or captured.

Stirling and Major Mordecai Gist took a contingent of approximately 270 men from the Maryland Regiment and repeatedly attacked the British defending the house in order to open a breach in the British lines and enable Washington and the rest of the Army to escape. After sustaining heavy losses, Major Gist and nine soldiers escaped. Stirling was captured and later released in a prisoner exchange for a British loyalist, Montfort Browne.

Reading an abbreviated account of the battle leaves out a lot of important facts. Why were the Marylanders left to sacrifice themselves? And why is an obscure figure like Montfort Browne worth mentioning?

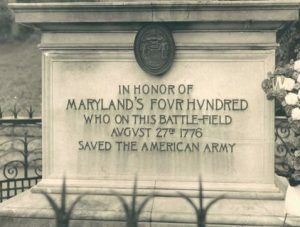

Maryland 400

The Maryland First Battalion consisted of 728 soldiers in 1776. They were among the best trained and armed. In those days, riflemen relied on bayonets for fast and close combat. Most of the Continental Army had no bayonets. The Maryland Battalion had bayonets and had drilled in their use. During the Battle of Brooklyn the Battalion sustained heavy causalities. By the time Washington ordered the retreat, the Battalion had dwindled to around 400 soldiers. That is the number that has been reported in histories of the battle and eventually accepted as a convenient round number to romantically compare to the three hundred Spartans who battled the invading Persian Army at the Battle of Thermopylae.

The Maryland First Battalion consisted of 728 soldiers in 1776. They were among the best trained and armed. In those days, riflemen relied on bayonets for fast and close combat. Most of the Continental Army had no bayonets. The Maryland Battalion had bayonets and had drilled in their use. During the Battle of Brooklyn the Battalion sustained heavy causalities. By the time Washington ordered the retreat, the Battalion had dwindled to around 400 soldiers. That is the number that has been reported in histories of the battle and eventually accepted as a convenient round number to romantically compare to the three hundred Spartans who battled the invading Persian Army at the Battle of Thermopylae.

Gist and Stirling led their troops into British fire, each time sustaining devastating casualties. Stepping over their fallen comrades, they continued to press on. Washington is reported to have exclaimed, ” “My God, what brave men I must this day lose!”

Those who sacrificed themselves whether wittingly or out of desperation to escape themselves allowed Washington to escape with his army. The entire revolution could have ended at the Battle of Brooklyn.

For a closer look at where the idea of the Maryland 400 came from click HERE.

256 Maryland Soldiers

After the battle for Brooklyn, it was believed that the British or Hessian troops dug a long trench and buried the fallen Maryland soldiers. For many years residents thought the graves were beneath a concrete parking lot around 9th Street and 3rd Avenue in Brooklyn, NY. The Department of Education even installed a plaque at the location.

After the battle for Brooklyn, it was believed that the British or Hessian troops dug a long trench and buried the fallen Maryland soldiers. For many years residents thought the graves were beneath a concrete parking lot around 9th Street and 3rd Avenue in Brooklyn, NY. The Department of Education even installed a plaque at the location.

For over 100 years after the battle, the land where the battle was fought remained farmland. Farmers reported digging up human bones occasionally as they tilled the land.

The Vechte-Cortelyou House was a sturdy structure designed to withstand attacks from native Americans. It changed hands several times after the war but it was razed and burned in 1897. A later reconstruction by the city used some of the stones from the original building and now it serves as a Department of Park’s and Recreation museum and comfort station.

The location of the grave of the 256 Maryland soldiers remained controversial until 2017 when the city hired the architectural contracting firm AKRF to excavate the parking lot. Nothing was found except the remains of a pit (outhouse). No bones or other artifacts were found.

Montfort Browne

The story of Montfort Browne is instructive. We think of ourselves as Americans. And when we think of the founding fathers and George Washington in particular, we think of the United States. But when the Revolution against England started, there were no United States; there were 13 colonies. Each colony was committed to the revolution to varying degrees and the citizens of the colonies saw themselves as citizens of each colony, not of a larger nation. Almost everybody was a loyal subject of King George III until they took the terrifying step to declare their allegiance to the traitors, whom we call now call patriots.

What we now think of as the American Revolution was in fact a civil war. And the greater war, after France and Spain joined to help “our side,” was in fact a global war. It became a rematch of the Seven Years’ War (1756–63) when France and Spain suffered defeat and loss of territory at the hands of the British. Our revered hero, General George Washington was a militia colonel who was sent to fight the French in the Ohio valley. He was defeated by the French and forced to sign a declaration in French that that was used as propaganda by the French to exacerbate hostilities between France and Britain, eventually leading to the Seven Years’ War.

King George did not view his war in the colonies as a war against a foreign enemy; it was an uprising among his loyal subjects. And indeed most of the colonists remained loyal in the beginning. Estimates are as high a 65% were loyal, 35% were sympathetic to the revolution, but only 10% were willing to die for their beliefs. Benjamin Franklin’s own son remained loyal to the British Crown and in 1782, he went into exile in Britain.

Montfort Brown was also a loyal subject of the crown, a British Army officer, Tory, land speculator in west Florida, and governor of the Bahamas from 1774 to 1780. In March of 1776 he had the misfortune of being take prisoner along with 12 other high ranking Bahamian officials and taken to Maryland by the American fleet. In those days of gentlemanly warfare among generals and high ranking officials, Browne and perhaps some of his cohorts were a perfect swap for the recently captured American general, Brigadier General William Alexander Stirling. Upon his release, Stirling was promoted to Major General.

By returning Stirling to the battlefield, the revolution gained back a general officer ranked variously as number 3 or number 4 after Washington himself.

Thomas Paine

When Thomas Paine published his ideas that culminated in the multiple versions of “Common Sense,” most colonists identified as British. Even those whose ancestors came from other countries like the Dutch who settled New York were fluent in English. The Foundation for Economic Education estimates that approximately 80% of men and 50% of women in New England were literate by 1776.” The high literacy rate may have directly contributed to the revolution considering the success of “Common Sense.”

Even those whose ancestors came from other countries like the Dutch who settled New York were fluent in English. The Foundation for Economic Education estimates that approximately 80% of men and 50% of women in New England were literate by 1776.” The high literacy rate may have directly contributed to the revolution considering the success of “Common Sense.”

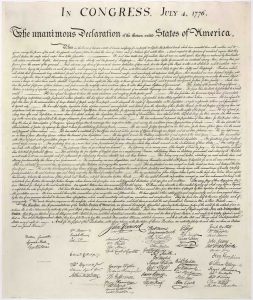

Published anonymously on January 10, 1776, it is amazing that the ideas in Common Sense were ratified in the language of the Declaration of Independence just six month later on July 4, 1776. In this excerpt, Paine makes the case that the Colonists are European Protestants and the New World is the Cradle of Liberty.

“But Britain is the parent country, say some. Then the more shame upon her conduct. Even brutes do not devour their young, nor savages make war upon their families; wherefore the assertion, if true, turns to her reproach; but it happens not to be true, or only partly so, and the phrase parent or mother country hath been jesuitically adopted by the king and his parasites, with a low papistical design of gaining an unfair bias on the credulous weakness of our minds. Europe, and not England, is the parent country of America. This new world hath been the asylum for the persecuted lovers of civil and religious liberty from every part of Europe. Hither have they fled, not from the tender embraces of the mother, but from the cruelty of the monster; and it is so far true of England, that the same tyranny which drove the first emigrants from home, pursues their descendants still. ”

Tyrannical American Government?

There is a large segment of American society, particularly on the political Left, who enlist Paine’s rhetoric to bolster their own grievances.

“…our calamity is heightened by reflecting that we furnish the means by which we suffer.”– Thomas Paine, Common Sense 1776

The Big Easy Magazine website proclaims itself as Unapologetically Progressive. Uniquely New Orleans. The writer boldly proclaims:

The current state of civil unrest must be viewed in the context of a tyrannical American government. When a group of people are being oppressed, American history has shown, that violence, riots, and revolution are predictable outcomes.

Asad El Malik, June 1st 2020

We cannot argue with the publication’s core values: Kindness Compassion Equality Love Justice Inclusiveness, however contradictory they may seem to violence, riots, and revolution. We do however strongly disagree with the premise of a tyrannical American Government.

Many of the grievances in the Big Easy story deal with local conditions, police departments under local control, not a tyrannical American government. Such hyperbole is uninformed by history, fact, and reason. The Constitution guarantees citizens’ right to petition the government for redress of grievances. Of course the easiest way to change things is to vote for qualified leaders in the first place, instead of the perpetually corrupt local governments that “furnish the means by which (they) suffer.”

Further Reading

The Black Lives Matter movement identified real injustice, both in current events and in the recent past. It appears that some of the violence accompanying protests was motivated by outside forces that have alternative agendas. Sadly this detracts from the message that seeks to correct racial injustice. It also takes away from the tremendous progress that has been made particularly since the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

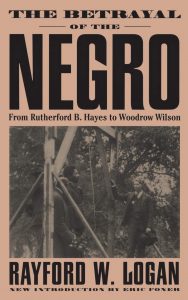

Rayford W. Logan argues that 1901 was the low point of black Americans’ status in society. His book, “The Negro in American Life and Thought: The Nadir,  1877–1901,” was published in 1954 and is now a collectors item. It was republished and expanded as “The Betrayal Of The Negro: From Rutherford B. Hayes To Woodrow Wilson,” in 1997.

1877–1901,” was published in 1954 and is now a collectors item. It was republished and expanded as “The Betrayal Of The Negro: From Rutherford B. Hayes To Woodrow Wilson,” in 1997.

A worse past is no justification for dismissing current problems. However, learning about the past helps us understand that real progress has been made and many brave people accomplished it by quietly writing books or being active politically. Change can be made without violence, riots, and revolution.

Community Discussion

Be respectful, but please speak your mind! We want a healthy discussion. There are no right or wrong answers here.